Our immune systems are very effective at protecting us from many pathogens that can cause diseases. When we get injured or when foreign matter enters our bodies, the immune system reacts by producing cells and antibodies that attack and eliminate pathogens. As the vertebrate immune system can take many forms and shapes dependent on what is required for effective defenses against pathogens, it is clearly plastic.

But are vertebrate immune systems also able to prepare themselves for possible future injury long before injury, before any pathogen enters the bloodstream? To address this question, I conducted a long-term experiment on the cichlid Pelvicachromis taeniatus. Predator attacks are clearly known to cause injury, and it would be beneficial for individual immune systems to prepare ahead of time before a predator attack actually occurs – so they can respond faster to injury.

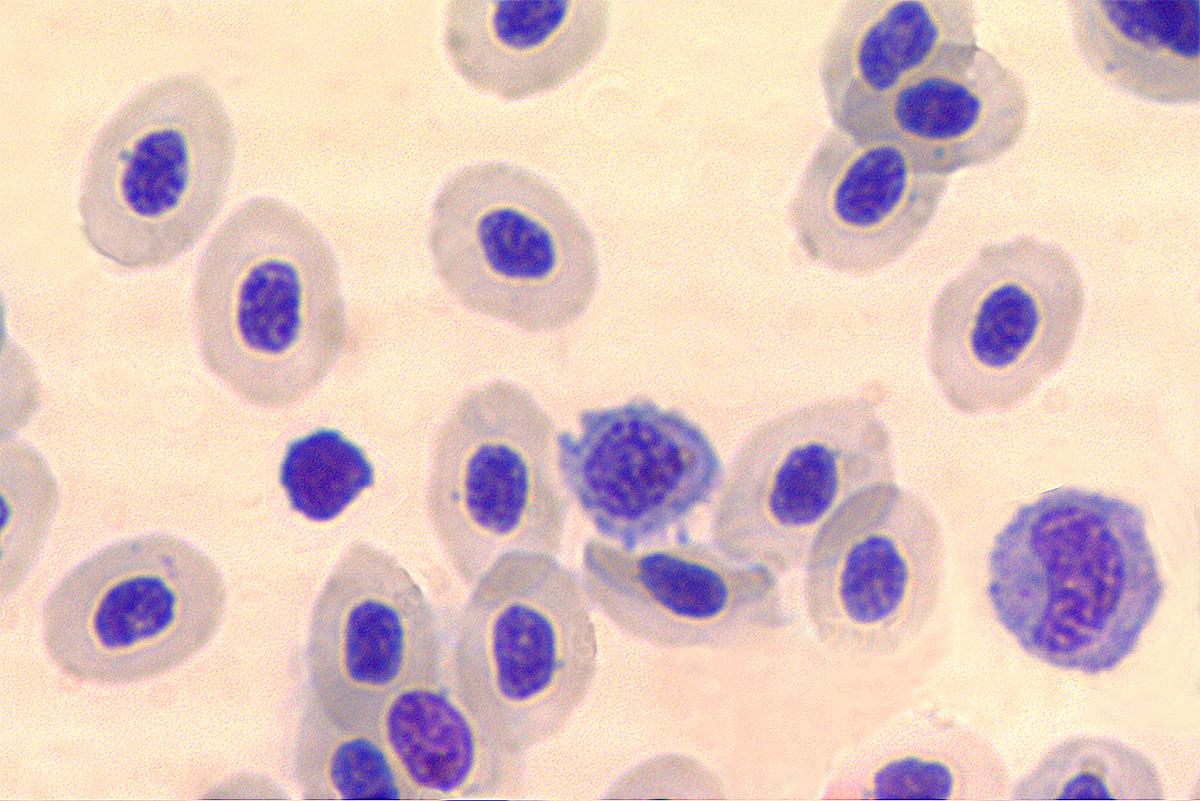

Over a four-year period, we exposed cichlids to either perceived high predation risk as communicated through conspecific alarm cues – which are perceived as an odor – or to a control treatment. Then, we sampled their blood, and assessed the number of different white blood cells.

Individuals that had been exposed to perceived predation risk had more white blood cells than controls. This was because they had almost twice as many lymphocytes as controls. Lymphocytes are the most frequent white blood cell type and include cells that directly attack and kill pathogens as well as those that produce antibodies. Thus, the presence of more lymphocytes in risk-exposed individuals suggests the immune system prepared itself for future injury.

However, the greater production of lymphocytes is not without cost. Greater cell multiplication rates also increase the risk of cancer such as leukemia. This is why it makes sense to boost lymphocyte production only when odors are perceived that suggest future attacks on the individual.

More detail about this study can be found at Oecologia, where it was recently published.